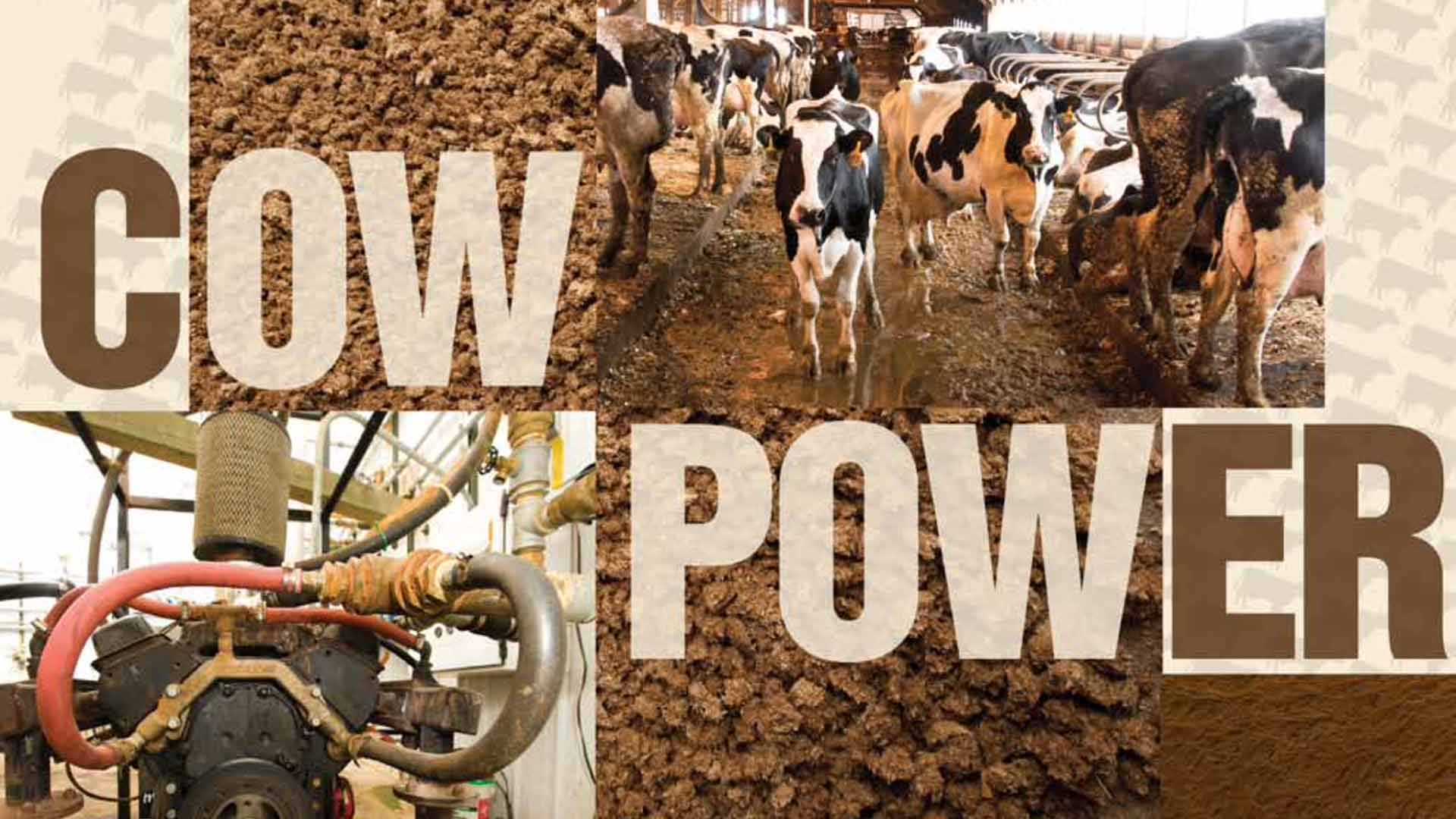

Brooten, Minn. — Jerry and Linda Jennissen and their cows are out to prove that large dairies aren’t the only ones with power.

A building attached to their dairy barn is filled with tanks, pipes and the constant hum of an engine burning biogas produced by an anaerobic digester.

Digesters are usually installed in large dairies, with 700 cows or more. Jennissen’s Jer-Lindy Farm, with 150 dairy cows, is being studied to see if average-size herds can be energy producers.

“The Minnesota Project received a Legislative Citizens Commission on Minnesota Resources grant to put a digester on a mid-sized farm,” says Jerry Jennissen. “After a lengthy process, it ended up here.”

“We wanted to see if the technology could work,” says Amanda Bilek, a former Minnesota Project employee who is now an energy policy specialist with the Great Plains Institute. “The goal was to test cutting-edge technology that could prove to be profitable for an average-size Minnesota dairy farm. We are learning a lot.”

Manure to biogas

In the fall 2007, building began on the digester that started producing electricity in May 2008.

Cow manure is scraped into a mixing pit twice a day where it is diluted with recycled water until the slurry is 6 to 8 percent solids. The manure is intermittently pumped into a 33,000 gallon tank where it remains for about five days. The sealed environment is maintained at a 100-degree temperature.

Bacteria in the digester converts manure organic matter to methane gas that is collected and pumped to a modified automotive engine built to run on natural gas or propane. The generator produces 40 kilowatts of electricity from the biogas. Electricity not used by the digester plant is sold to Stearns Cooperative Electric Association. The leftover digester solids are reused for cattle bedding.

Jennissen says the manure alone doesn’t generate enough biogas in the digester, so whey from an area milk processor is added to boost biogas output. “We tripled our gas production by adding whey,” Jennissen says.

Steep learning curve

Because most digester technology is designed for large-scale operations, Jennissen’s digester has had challenges. It was difficult to find an engine sturdy enough to handle the rigors of round-the-clock operations. The Jer-Lindy digester is on its third engine.

“One of the biggest assets for big digesters is that you can find large generator sets to operate on biogas,” says Joe Borgerding, a local electrician and mechanic who is designing an efficient gen set for smaller digesters. “Most engines built to run on the smaller amount of biogas aren’t designed to run long-term. They aren’t robust enough.”

Despite the challenges, identifying technologies and processes that will make smaller-scale digesters feasible could boost rural economies as well as dairy producers.

“The average-size dairy herd in Minnesota is 104 cows,” says Bob Lefebvre, Minnesota Milk Producers executive director. “The idea of having a sustainable system that works economically in an operation of this size would be attractive to many dairies. We would have more energy producers.”

Small-scale technology

AURI and the Center for Producer-Owned Energy became involved this year to help pinpoint how raw biogas impacts engines and to assist with developing technologies for smaller-scale generators.

“So much digester technology is large scale, but developing what is needed for it to be feasible in smaller operations would spur new development and build a new economy,” says Jen Wagner-Lahr, AURI project director. “There will also be options in how the energy is delivered,” whether as biogas or electricity, she adds.

Unlike other renewable-energy sources, such as solar and wind power, anaerobic digesters can maintain power 24 hours a day. They also could use waste streams from dairy operations and local processors.

“There is a real environmental benefit,” Jennissen says. “We are creating power plus treating waste.”